Like a lot of people my age, I spent a good chunk of the 90s obsessed with the Pixies, the band out of Boston who defined, for many, the alternative rock genre (also, I’m old enough to remember when alternative was called “college rock”). I listened to their album Doolittle on repeat for probably three months, and it changed everything I thought about rock and roll at the time.

The singer was a mysterious figure calling himself Black Francis. We didn’t know much about him, back then when you couldn’t just Google an artist and find out what they ate for breakfast today. We only knew that he sang every song like his shirt was on fire.

Eventually, of course, the Pixies broke up, and after a few years Black Francis started going by Frank Black and putting out a string of incredible solo albums, some on his own and some with his backing band, as Frank Black and the Catholics. Between 1998 and 2005 he released seven albums that I consider basically perfect, not a dull moment or a bad track:

Frank Black & The Catholics

Pistolero

Dog in the Sand

Black Letter Days

Devil’s Workshop

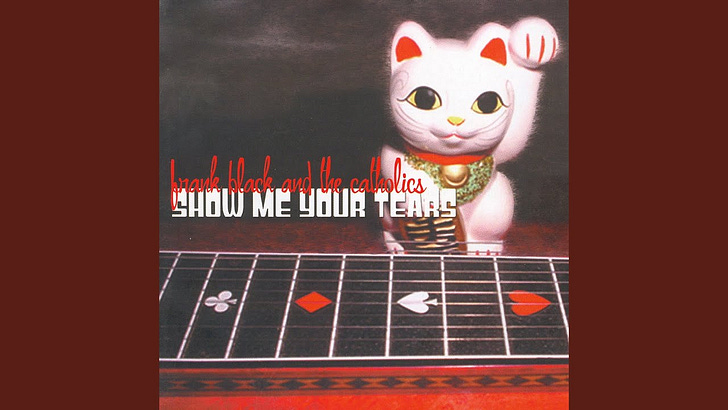

Show Me Your Tears

Honeycomb

Of those, Dog in the Sand is probably my favorite, with tracks like “The Swimmer,” “I’ve Seen Your Face,” and “If It Takes All Night.” But if I’m looking for one song to showcase his songwriting skills, my mind goes immediately to the weird moodiness of “This Old Heartache,” on Show Me Your Tears. Please give it a listen before you read further:

The lovely lyrics and sad, introspective melody originally drew me in, and I considered it a top-shelf song* even before I tried to play it on the guitar myself. Once I looked at the chords, I realized how and why it works so effectively.

First of all, the chord changes are like nothing else you’ll see in any pop song. Even the intro has these baffling runs like F#m - F - G#m - G. Where are these sequences coming from? Is this a jazz song?

And then look at his willingness, not just to use in passing, but to actively lean on the weird, impossible augmented fourth change: On “my dear, you cannot soothe this old heartache” the chords are E7 - Bb - E7, and later when he shifts keys (more on that in a moment), the same melodic line is carried by C# - G - C#.

I learned everything I know about music theory by reading and playing the chord changes to countless thousands of songs by everyone from the Beatles to Ella Fitzgerald to Steely Dan to Bad Brains, and no one puts chords together like this. Or if they do, it’s a punk band like the Dead Milkmen who are doing it for the intentional discordance. But Frank Black does it because it’s what his melody requires at that moment, and, like Dave Brubeck playing in 5/4 time, he makes it work so smoothly that the casual listener never even notices anything is unusual.

(He pulls strange tricks with chords in other songs as well. A second verse will keep the melody but reverse the chords, or a Cm - C# change becomes C - C#m the second time around. It’s mesmerizing when you start digging into it.)

About those key changes. The first two times through the melody, the song is in A minor. Then after a musical break from 1:27 to 2:14, he comes in singing the main melody (the only melody, as the song has no chorus) again, but this time it sounds a little different—it sounds like he’s putting more urgency into the vocals, but actually he’s switched keys. Not from A minor to B minor, or to C major which would also be an obvious choice, but rather now he’s singing it in F# minor. Why? Because it sounds right! How did those chords transition so smoothly? Only the ghost of JS Bach can answer that.

And what happens the next time around? Now he’s singing the same melody in the same key, but he's singing it an octave down, in a register that is obviously lower than he’s comfortable with. In fact he’s intentionally chosen a key that he can’t sing in, so that we can hear him straining to reach the lowest notes. (Liz Phair used to do something similar.) This rumbling final verse plays like it’s coming straight from his belly, bypassing his vocal cords entirely.

The effect of all this is a song that feels both melancholy and aggressively uncomfortable, something sad and regretful but also totally unwilling to change to suit your idea of what it ought to be. And that’s the real genius, the way the structure of the piece meshes perfectly with the lyrical content:

But if I should leave this state,

There’s nothing you can do.

Notes:

I mentioned “top-shelf songs” above. I long ago gave up trying to pick a favorite song. It’s futile, and more to the point it’s dishonest. Ranking songs, or movies, or foods, etc., is just not how these things work. Is “September Song” better than “Cult of Personality”? It’s a meaningless comparison, because both of them are perfect. What I came to realize is that there is a group of songs (and photographs, and books, etc.) that are perfect and we shouldn’t try to set one against the other. These are top-shelf songs, and “This Old Heartache” is absolutely one of them.

I saw an interview with David Bowie years ago. I think it was in the extras on a DVD of a Pixies concert. The interviewer asked Bowie about Frank Black and Bowie said something like “He’s absolutely one of the great American songwriters, up there with Gershwin and Cole Porter and Stephen Foster.”

Related: Streaming is great, and convenient, but I miss the physical aspects of analog media. Album art was great, but what I really miss is liner notes. You never knew what you were going to find in there.

I kinda thought that this Frank Black was trying to channel his inner Leonard Cohen on this song and it was fascinating. I'm happy to have been introduced to his music today.